Queen Charlotte appears in Netflix’s popular Bridgerton series as a fiercely haughty and powerfully headstrong monarch. The prequel spin-off series, Queen Charlotte: A Bridgerton Story, is only increasing our insatiable love of the character. With her expansive Pomeranian brood and snuff-tobacco habit, how close is Bridgerton’s Queen Charlotte to history’s real Georgian queen consort?

Top 10 Scandalous Snippets of Georgian Gossip

Sophia Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1744—1818) was just 17 when she was selected to be the bride of King George III. Leaving her small dukedom in northern Germany behind, she travelled to England to begin her new life as queen consort.

She left an enduring impact on British culture and society, from her introduction of the Christmas tree to her influence on music and fashion. But her reign was also central to its fair share of rumours and hearsay. We’ve gathered the top 10 most scandalous secrets and snippets of Georgian gossip to unveil the real Queen Charlotte.

Beauty Queen or Pug-Ugly?

Our queen is neither a wit nor a beauty. (…) She loves domestic pleasures; is fonder of diamonds than the Queen of France; as fond of snuff as the King of Prussia; is extremely affable, very pious, and is praised by all the world.

—The Annual Biography and Obituary for the Year 1821, Volume V

Charlotte, the ugly, shrewish, cantankerous wife of George III, fancied the pug, perhaps because its visage was as strong-featured as her own.

—Herbert Compton, The Twentieth Century Dog (Non Sporting) Compiled From The Contributions Of Over Five Hundred Experts, Vol. I, 1904

She is not tall nor a beauty. Pale and very thin; but looks sensible and genteel. Her hair is darkish and fine; her forehead low, her nose very well, except the nostrils spreading too wide. The mouth has the same fault, but her teeth are good. She talks a great deal, and French tolerably.

—Horace Walpole, The Letters of Horace Walpole, Volume 3

The Queen Behind ‘Mad’ King George

BETROTHAL ANNOUNCEMENT OF KING GEORGE III

‘I am come to a resolution to demand in marriage the Princess Charlotte of Mecklenburg Strelitz; a princess distinguished by every eminent virtue and amiable endowment, whose illustrious line has constantly shewn the firmest zeal for the Protestant religion, and a particular attachment to my family.’

—John Watkins, Memoirs of Her Most Excellent Majesty Sophia Charlotte Queen of Great Britain, 1819

All the world knows the story of his malady. History presents no sadder figure than that of the old man, blind and deprived of reason, wandering through the rooms of his palace, addressing imaginary parliaments, reviewing fancied troops, holding ghostly courts.

—Arthur Mee, ‘The Saddest Story of the English Throne’, One Thousand Famous Things, 1937

Bridgerton lightly touches on the deterioration of King George III’s mental health, which broke down the royal couple’s joyous, loving marriage.

Often referred to as the ‘Mad King’, the cause of his suffering remains unknown, though bipolar disorder or porphyria, a blood disease that affects the nervous system, have been posited as possible explanations.

In 1789, as his behaviour became increasingly erratic and unsuitable, Queen Charlotte was thrown into sorrow, and the couple spent much of the remainder of their lives apart.

Marie Antoinette’s Closest Confidant

Upon her arrival in England, Queen Charlotte left her beloved family behind and sought solace in the company of close companions, fostering relationships with the ladies of the court and other European aristocracy. Notably, she developed a close bond with Marie Antoinette, the Queen of France, sharing an ardent enthusiasm for music and maintaining an intimate correspondence until the latter’s trial and subsequent execution in 1793.

Friends, Gossip, and Ladies of the Court

Much like Bridgerton‘s infamous Lady Whistledown, many of the individuals with whom Queen Charlotte associated made concerted efforts to chronicle their experiences within the royal court. From posthumous journals to novelised accounts, several of her friends have disclosed details regarding the queen’s private life, not all of them kind.

LADY MARY COKE

Lady Mary Coke (1727—1811) was an English noblewoman who kept detailed letters and journals observing the people she encountered in the royal court.

What strikes one particularly is the singularly low standard of morals, particularly among the ladies, and the positive effrontery that carried off the innumerable breaches of propriety and good conduct. (…) Though the queen was presumed to be a purist in regulating her court, she seemed to have been compelled to accept this state of things in a business-like fashion

—Percy Hetherington Fitzgerald, The Good Queen Charlotte, 1899

LADY ANNE HAMILTON

Lady Anne Hamilton (1766–1846) was a writer and a lady-in-waiting to Caroline of Brunswick, Queen Charlotte’s eldest son’s estranged wife.

Who was Queen Charlotte, that the eyes of the public should be blinded, or their tongues mute, upon this apathy and unfeeling demeanour to the king, her husband, who had raised her from comparative poverty to affluence and greatness? (…) Every one seemed afraid of impugning the character of a queen, so celebrated for amiability and virtue!

—Lady Anne Hamilton, Secret History of the Court of England, from the Accession of George the Third to the Death of George the Fourth, 1832

FANNY BURNEY

Frances Burney (1752—1840) was an English novelist, best known for her satire as well as her diaries. Her most-celebrated work is Evelina (1778), but the highly regarded author also found success in the royal court as Queen Charlotte’s Keeper of the Robes.

Of the king and queen (…) even Fanny, with all her loyal partiality, could make no more of them than a well-meaning couple, whose conversation never rose above the commonplace.

—Fanny Burney, The Diary and Letters of Madame D’Arblay, Volume I, 1842

Regency Fashion Trendsetter

The Georgian Era, which spanned from 1714—1837 in Great Britain, encompassed the reigns of George I, George II, George III, George IV, and William IV. During this period, the fashionable attire amid the upper classes comprised of gloves, flowing gowns, stiff corsets, waistcoats, and breeches. The Regency Era began in 1811 as George III became incapacitated with illness, and his eldest son, the Prince of Wales, became Regent.

The Regency Era brought about a shift in fashion, introducing the delicate and fluid chemise gown, featuring raised waistlines and shorter, puffed sleeves in lieu of the previous long, tight fit. Amid this transition, Queen Charlotte seemed to have shown a marked concern for the hairstyles of her ladies, and even enforced a ban on plumed coiffures in the court.

LONDON, APRIL 15.

It is become a general fashion with the women to wear large feathers on their heads, which often hinder their entrance into their apartments; and which fashion now so increases, that we may truly call them, not the feminine, but the feathered sex. The Queen, the example of her sex in every virtue, has forbidden any of the plume-headed ladies to appear at court.

—John Watkins,

Memoirs of Her Most Excellent Majesty Sophia

Charlotte Queen of Great Britain, 1819

PLUMES WERE WORN

These were forbidden at Court by Queen Charlotte, but without avail. As the ‘‘head’’ diminished in size the number of plumes increased to three in number, as we see in many old prints of the period, such as those of the old Bath assembles in 1787, when the leg-horn picture hats and hair in curls were worn on the parade.

—Napanee Express, 19 May 1911

A Deadly Love of Lace

In the next reign, George III and Queen Charlotte often condescended to become sponsors to the children of the aristocracy. To one child, their presence was fatal.

In 1778 they ‘stood’ to the infant daughter of the last Duke and Duchess of Chandos. Cornwallis, Archbishop of Canterbury, officiated. The baby, overwhelmed by whole mountains of lace, lay in a dead faint. Her mother was so tender on the point of etiquette, that she would not let the little incident trouble a ceremony at which a king and queen were about to endow her child with the names of Georgiana Charlotte. As Cornwallis gave back the infant to her nurse, he remarked that it was the quietest baby he had ever held.

Poor victim of ceremony! It was not quite dead, but dying; in a few unconscious hours it calmly slept away.

—A Gossip on Royal Christenings, Cornhill Magazine, 1864

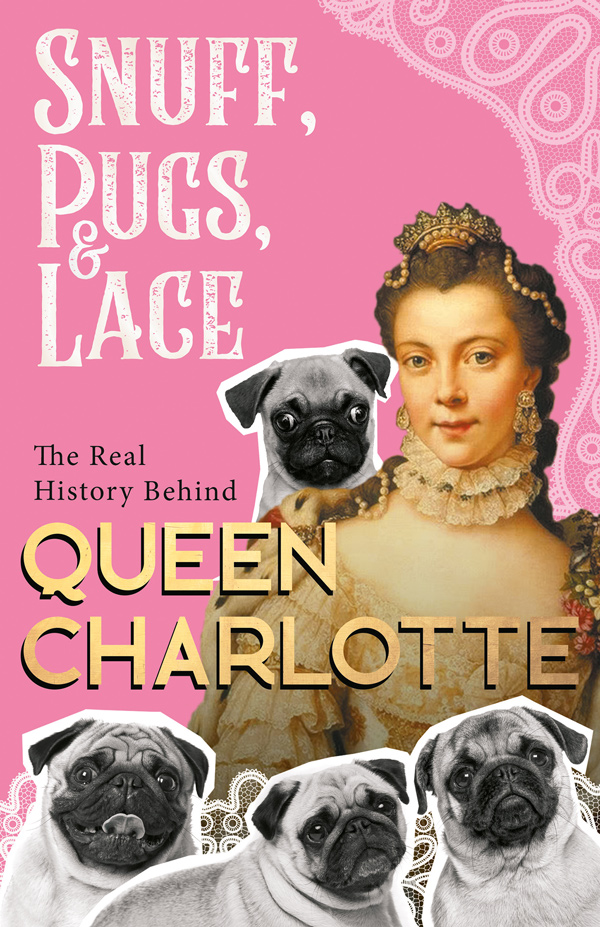

Dogs: A Queen’s Best Friend

The tradition of Great Britain’s queens having a fondness for dogs is well established. Elizabeth II (r. 1952—2022) was a renowned keeper of corgis, and the loyal breed became synonymous with her reign. Likewise, Queen Victoria (r. 1837—1901) shared her home with several dog breeds, most notably the spaniel, but also collies, dachshunds, and pugs.

Queen Charlotte was no exception to this rule and had a strong affinity for pugs. She was never far from her favoured lapdogs and also had a known fondness for Pomeranians, which she brought with her to England prior to her marriage to George III.

Old Snuffy and Caricatures

Snuff is the product of finely ground or sometimes pulverised tobacco leaves, resulting in a tobacco product that can be sniffed, snorted, or snuffed. It allows nicotine to be consumed without inhaling smoke. Particularly common during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, snuff-taking was popular amongst the upper classes.

Queen Charlotte was a prominent snuff user, earning her the sobriquet ‘Snuffy Charlotte’, or more affectionately referred to by her sons as ‘Old Snuffy’. The Queen had a dedicated room at Windsor Castle for her snuff and snuff accessories. Several paintings and caricatures of her feature a snuff box.

The first eminent woman to write her name on the scroll of English women snuff-takers was Queen Charlotte, the wife of George III. She took snuff in such quantities as to make strong men turn pale at the thought of it.

—C. W. Shepherd, ‘Snuff-taking Ladies’, Snuff—Yesterday and Today, 1963

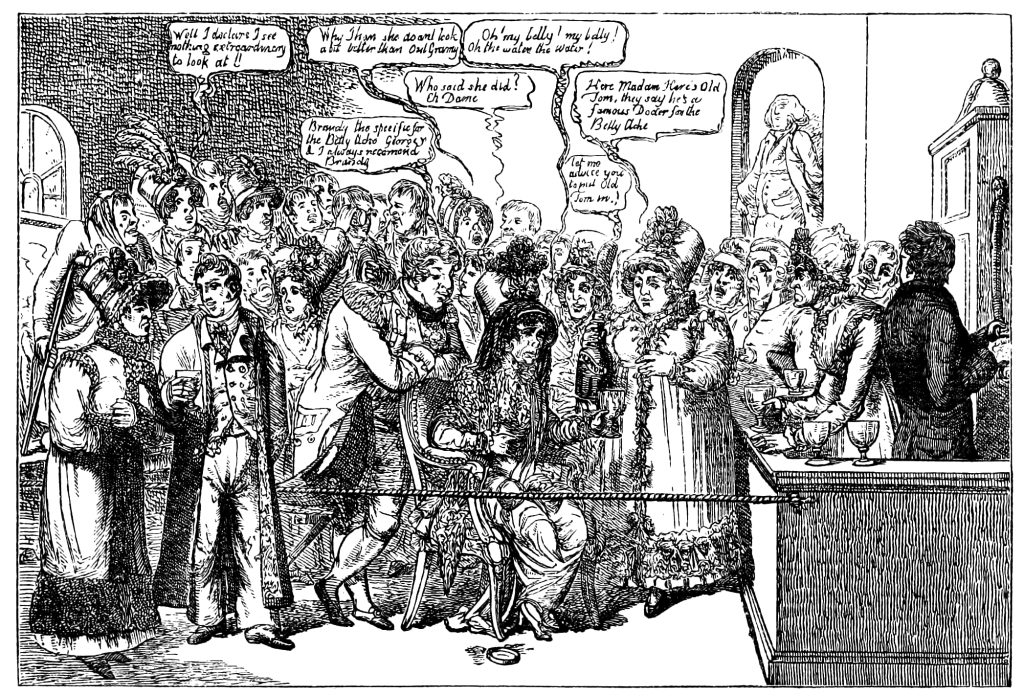

A well-drawn caricature, published by Fores in February, 1818, and entitled, A Peep at the Pump Room, or the Zomersftshire Folk; in a Maze, shows us a singularly ugly old woman habited in a wonderful bonnet, and clothes of antiquated make and fashion, drinking the Bath waters in the midst of a circle of deeply interested and curious gazers.

This poor old woman, who looks very like an old nurse, is no less a person than Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, Queen of George the Third, who, in failing health and rapidly drawing towards the close of her earthly pilgrimage, had been recommended by her physicians to try the effect of the Bath waters. (…) One of her well-known habits is referred to by the snuff-box which lies at her feet.

—Graham Everitt, English Caricaturists and Graphic Humourists of the Nineteenth Century, 1893

Patron of the Arts

A known patron of the arts, Queen Charlotte often indulged in beautiful music compositions and was herself a gifted harpsichord player and singer. In 1864, the celebrated composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, the just eight years of age, was invited to Buckingham House to perform for both George III and his queen consort. Mozart performed the works of esteemed composers including George Frideric Handel, Johann Sebastian Bach, and Carl Friedrich Abel on sight. He then accompanied the Queen while she sang an aria. In 1765, Mozart’s Opus 3 were dedicated to the Queen, indicating her influential role in the promotion of the arts.

Six years after Handel’s death, the seven-year-old Mozart in London dedicated his violin sonatas to Queen Charlotte in the hope that under Her Majesty’s protection ‘je deviendrai immortel comme Haendel et Hasse’ [‘I will become immortal like Handel and Hasse’].

—Donald Francis Tovey, The Forms of Music, 1943

Christmas Tree Mastermind

Queen Charlotte is credited with introducing the Christmas tree to Great Britain, having brought the Mecklenburg-Strelitz tradition of adorning a tree with baubles, fruit, sweets, candles, and tinsel to Queen’s Lodge, Windsor. She hosted a Christmas party for the children of the families residing in Windsor, and allowed them to take their share of the tree’s treats. Each child went home with a new toy and sugary lips. This initiated the custom of Christmas tree decoration among the British aristocracy.

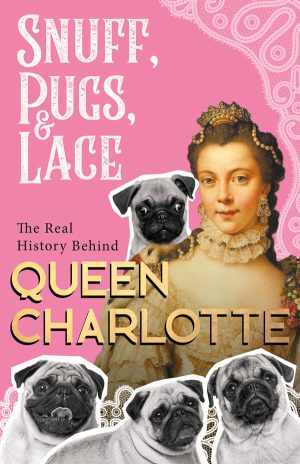

Discover more about the real queen behind Bridgerton‘s Queen Charlotte:

A fascinating insight into the life of Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, Britain’s longest reigning queen consort. This unique collection of essays, poetry, and artwork reveals the true history behind the brilliant wife of King George III.