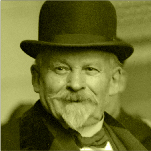

Émile Coué de la Châtaigneraie was born on 26

th February 1857, in Brittany, France. He was a French psychologist and pharmacist who introduced a popular method of psychotherapy and self-improvement known as ‘optimistic autosuggestion.’

Coué’s family, from the Brittany region of France and with origins in French nobility, had only modest means. A brilliant pupil in school, he initially studied to become a chemist. However, he eventually abandoned these studies as his father, who was a railroad worker, was in a precarious financial state. Coué then decided to become a pharmacist and graduated with a degree in pharmacology in 1876. Working as an apothecary at Troyes from 1882 to 1910, Coué quickly discovered what later came to be known as the placebo effect. He became known for reassuring his clients by praising each remedy’s efficiency and leaving a small positive notice with each given medication.

In 1901 he began to study under Ambroise-Auguste Liébeault and Hippolyte Bernheim, two leading exponents of hypnosis. He greatly enjoyed these studies, taking much inspiration and in 1913, Coué and his wife founded

The Lorraine Society of Applied Psychology. His book

Self-Mastery Through Conscious Autosuggestion was published in England (1920) and in the United States (1922). Although Coué’s teachings were, during his lifetime, more popular in Europe than in the United States, many Americans who adopted his ideas and methods, such as Norman Vincent Peale, Robert H. Schuller, and W. Clement Stone, became famous in their own right by spreading his words.

The application of his mantra-like conscious autosuggestion, ‘Every day, in every way, I’m getting better and better’ (

Tous les jours à tous points de vue je vais de mieux en mieux) is called Couéism or the Coué method.

Coué noticed that in certain cases he could improve the efficacy of a given medicine by praising its effectiveness to the patient. He realised that those patients to whom he praised the medicine had a noticeable improvement when compared to patients to whom he said nothing. This began Coué’s exploration of the use of hypnosis and the power of the imagination. Coué thus developed a method which relied on the principle that

any idea exclusively occupying the mind turns into reality, although only to the extent that the idea is within the realm of possibility. For instance, a person without hands will not be able to make them grow back. However, if a person firmly believes that his or her asthma is disappearing, then this may actually happen, as far as the body is actually able physically to overcome or control the illness.

Thanks to his method, which Coué once called his ‘trick’ patients of all sorts would come to visit him. The list of ailments included kidney problems, diabetes, memory loss, stammering, weakness, atrophy and all sorts of physical and mental illnesses. According to one of his journal entries (1916), he apparently cured a patient of a uterus prolapse as well as migraines. Cyrus Harry Brooks (1890–1951), author of various books on Coué, claimed the success rate of his method was around 93%.

Despite these apparent successes, many remained sceptical however. After Coué made a trip to Boston, the

Boston Herald waited six months and then revisited the patients he ‘cured’ and found most initially felt better but soon returned to whatever ailments they previously had. Few of the patients would criticise him however, stating he seemed incredibly sincere in what he tried to do.

Nonetheless, the Herald reporter concluded that any benefit from Coué’s method seemed to be temporary and might be explained by being caught up in the moment during one of Coué’s events.

Despite these criticisms, Coué was indeed very sincere, and treated as many patients as he could, in groups, free of charge. His

Lorraine Society of Applied Psychology was considered to represent a second

Nancy School (an establishment centred on hypnosis and psychotheraby, set up in 1866 by Coué’s former teacher, Ambroise-Auguste Liébeault). After a lifetime of work in psychology and pharmacy, Coué died on 2

nd July 1926, aged sixty-nine.