A famous American poet and essayist, born in Boston, Mass., May 25, 1803. His parents were the Rev. William Emerson and Ruth Haskins, and from them he received the training that the better class of New England parents bestowed upon their children. His boyhood was passed mainly in Boston. At the age of twenty be was graduated from Harvard College, and taught school for a time; then, like a large number of the educated youth of New England at that time, he studied for the ministry. He was ordained March 11, 1829, and became the colleague of Rev. Henry Ware, pastor of the Second Church (Unitarian) of Boston. In September of the same year he married Miss Ellen Louisa Tucker, who died in February, 1832. Shortly after his association with Ware the latter retired from active service and Emerson became pastor of the church, one of the foremost in New England. On September 9, 1832, however, he resigned his office, saying, in his farewell sermon, that he had ceased to regard the Lord’s Supper as a necessary rite, and that he was unwilling longer to administer it. Up to that time he had been known as a rather able, earnest, and pleasing preacher; he now entered upon his lifelong career as lecturer and essayist.

In the tall of 1833 he took his first trip to Europe, where he visited Sicily, Italy, France, and England, and met several well-known Englishmen, among them Landor and Carlyle. In September, 1835, he married Miss Lidian Jackson. The winters of 1835, 1836, and 1837 were marked by aeries of lectures, delivered in Boston, on “English Literature,” “The Philosophy of History,” and “Human Culture.” His more elaborated statement of belief, however, was to be found in his first published book,

Nature (1836), given out anonymously, but soon attributed to him. The volume had a small sale and received almost no popular notice, but it was important as an exposition of the basis of Emerson’s philosophy, and was accepted by such men as Carlyle as worthy doctrine. Briefly, it was a phrasing of the idealist view of human life, as opposed to the materialist, then common in England and America, and the Calvinist dogma, then still pervasive in New England, and he made the essay a plea for individual freedom. The following year, on August 31st, Emerson delivered the Phi Beta Kappa oration at Harvard College on “The American Scholar.” This was called by Holmes the ‘intellectual declaration of independence’ for America. Containing, in general, the lofty ethical principles of the author, it is, in particular, a sober and earnest exhortation of his hearers to lead their lives with thoughtfulness, austerity, and self-trust, not leaning for support on the traditions and precepts of the past, but cleaving a way independently in the present. The following year was also notable for proclamations of emancipation. July 15th he delivered an address before the students of the Divinity School at Cambridge expressing his belief in the validity of individual thinking in religious affairs, and on the 24th of the same month he set forth the same general point of view at Dartmouth College, New Hampshire, in a lecture called “Literary Ethics.” The first of these incited a warm and widespread controversy, in which Emerson, as usual, took no active part. Throughout his life he never did more than state his views in his own vigorous and winning language, content to let others carry on the discussion which he might have aroused, or body forth in some practical form the impulse which he had given them.

In 1841 the first series of his

Essays appeared. The volume contained several of the papers which have remained of all his work the most popular. It comprised “History,” “Self-Reliance,” “Compensation,” “Spiritual Laws,” “Love,” “Friendship,” “Prudence,” “Heroism,” “The Over-Soul,” “Circles,” “Intellect,” and “Art.” The second series of Essays appeared in 1844, containing such titles as “The Poet,” “Manners,” “Character.” In the interval between these two volumes Emerson had done much writing for the

Dial, the organ of New England idealism, or Transcendentalism as it was called. The paper was started in 1840 with Margaret Fuller as editor. Emerson himself succeeded her and remained editor till the collapse of the enterprise in 1844. With the other and better-known experiment of the Transcendentalists, the Brook Farm Community, Emerson had little to do. In 1847 appeared the first volume of Emerson’s poems, many of which had been published in the

Dial during its brief existence. In the same year be wrote the editor’s address for the newly founded

Massachusetts Quarterly Review, but did no further writing for it. In October he set sail for Europe for the second time. He delivered in England a series of lectures, some of which he gathered together in a volume entitled

Representative Men (1850). The subject suggests Carlyle’s

Heroes and Hero-Worship of ten years before; but the treatment of the subjects and the manner of approaching them are different. With Carlyle, the hero, be it in war or in letters, is the man who molds the way of the world; with Emerson the representative man is so called simply because he stands for an ideal of individual integrity — a character whence springs his worth. The journey to Europe also resulted in 1856 in a brilliant book of travel,

English Traits. In 1860 appeared

The Conduct of Life, a volume of essays on such subjects as “Power,” “Wealth,” “Fate,” and “Culture.” This was followed in 1867 by a collection of poems, which had previously been published in the

Dial and the

Atlantic Monthly, entitled

May-Day and Other Pieces, and in 1870 by another volume of ethical essays,

Society and Solitude. During the winters of 1868-70 Emerson delivered a series of lectures at Harvard College on the

Natural History of Intellect, which were posthumously published (1893). He made his third and last voyage to Europe in 1872. From about this time on his memory began to show signs of giving way, and, though he retained to the end of his life his command of his general ethical principles, his work after 1875 was fragmentary and scattering. In 1874 he made a collection of favorite poems, which he called

Parnassus, and the following year his last volume of essays,

Letters and Social Aims, appeared. A revised edition of his poems followed in 1878, and the same year were published a lecture on the “Sovereignty of Ethics,” and one on the “Fortunes of the Republic.” His death, which came after a short illness, occurred at Concord, Mass., April 27, 1882.

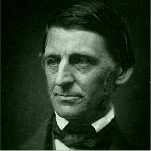

Emerson is described as tall and slender. He was nearly six feet in height and weighed about 140 pounds. He was not erect in carriage. His head was rather small in dimension, long and narrow, but lofty and symmetrical. “His face,” says Holmes, “was thin, his nose somewhat accipitrine, casting a broad shadow; his mouth rather wide, well formed and well closed, carrying a question and an assertion in its finely finished curves; the lower lip a little prominent, the chin shapely and firm. His whole look was irradiated by an ever-active inquiring intelligence, His manner was noble and gracious.” His personal habits were of the simplest sort, but were in no wise ascetic. He is said to have been somewhat oppressed by a feeling, not uncommon among New Englanders, of the more refined sort of physical insufficiency; and this trait may account for the fact that he rarely gave himself to active measures, but chose to live the contemplative life.

Emerson takes rank among the foremost writers of his time. All his prose, with the possible exception of one or two chapters in

English Traits and a few biographical sketches, may be strictly called essays. They represent a point of view of singular unity and persistence, and the chronology is really unimportant. Possibly the addresses printed in the volume called

Nature, together with that tract, all of which were written before 1845, represent a slightly more enthusiastic and zealous spirit than the later essays, and are rather more specific in subject. But, in the main, all the essays set forth a constant and enthusiastic belief in the value of individuality and the need of every man’s planting himself in the ground of his own consciousness and natural affection. Being himself a man of many intuitions and of wonderful vigor in phrasing them, he is to be regarded as a prophet rather than as a philosopher. He sought to construct no system, but stood for a constant idealistic impulse. What he wrote was not based primarily on experience, nor did he ever write as the so-called man of the world.

Emerson’s poetry is written from much the same point of view as his prose. While his contemporaries and friends among American poets were variously expressing themselves, as Poe in the search for beauty, or Longfellow in the phrasing of generous truisms and romance, or Whittier in his anti-slavery verse, or Holmes in his graceful occasional way. Emerson was uttering his feeling for the innate morality of the universe. The number of his poems is not large, for he wrote only when the mood prompted him, and not systematically. Few of his poems are long, but one is narrative, and almost all may be termed philosophical and reflective. They are by no means so popular as those of Longfellow or of Whittier; but among them are to be found some of the best poems that America has produced. Among the best-known are: “The Sphynx,” “The Problem,” “Hamatreya,” “The Rhodora,” “The Bumblebee,” “The Snowstorm,” “Woodnotes,” the “Threnody,” in commemoration of the death of his young son, the “Concord Hymn,” “Brahma,” “Terminus,” and the quatrain “Sacrifice.”

Emerson has been the subject of much criticism. That of an adverse sort censures him for relying chiefly or altogether on his intuitive consciousness instead of submitting his generalizations to the test of reason. Though gifted, to a very unusual among men, with a genius for piercing through appearances, he seldom or never took the trouble, say the rationalists, to analyze these vivid impressions with a view to ascertaining their verity. The consequence is that, though some of his work is fresh and wholesome in its truth-bearing qualities, much of it is obscure and unsubstantiated in the common experience of mankind. Another criticism somewhat akin to this is directed at his frequent superficiality, born of the same failure to verify statements by patient investigation. In consequence of this trait, his work is very uneven, disjointed, and formless. It is an agglomeration of detached sentences and epigrams, rather than a reasonable and consecutive presentation of truth. Finally, it is charged that his influence on his immediate followers was to cultivate a frequently epigrammatic and obscure manner of uttering platitudes and shallow thought, and that, in the main, he has retarded in America the growth of reasonable thinking processes. On the other hand, even his severest critics would admit that his influence has largely been wholesome. That influence has certainly been vast; no other American man of letters, probably, has been so potent a source of inspiration to his fellows. Coming at a time when the general tendency in America was toward a belief in material happiness, he taught that a man has also a spring of joy and hope in his inner consciousness. He stimulated men to a better faith in themselves, induced them to rely less on number, masses, and externals. Except in a few specific counsels, as about the reading of books, he rarely uttered a particular dogma, but stood generally for a large and dignified attitude toward life. He was a firm believer in the inner goodness of his country and of his fellow-citizens.

Emerson’s manner is unfailingly characteristic and original. He uses homely, simple language, racy of the soil of New England, very specific in its wealth of imagery, but never crude. His writing is almost always lively, but never fails to betray the calm and dignified spirit of the writer. It is often disjointed and often uneven, epigrammatic and choppy, but not infrequently contains a passage of great power and beauty. Many of his sayings, as “Beauty is its own excuse for being,” and “A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds,” are household phrases, and of longer passages few anywhere are more forcible than such as that on the use of books, in “The American Scholar,” or the closing paragraphs of his “Lecture on the Times.” The precepts of such essays as “Self-Reliance” may be said to be part of the mental marrow of every educated man in America.

A Biography by William Peterfield Trent,

The New International Encyclopædia, 1905