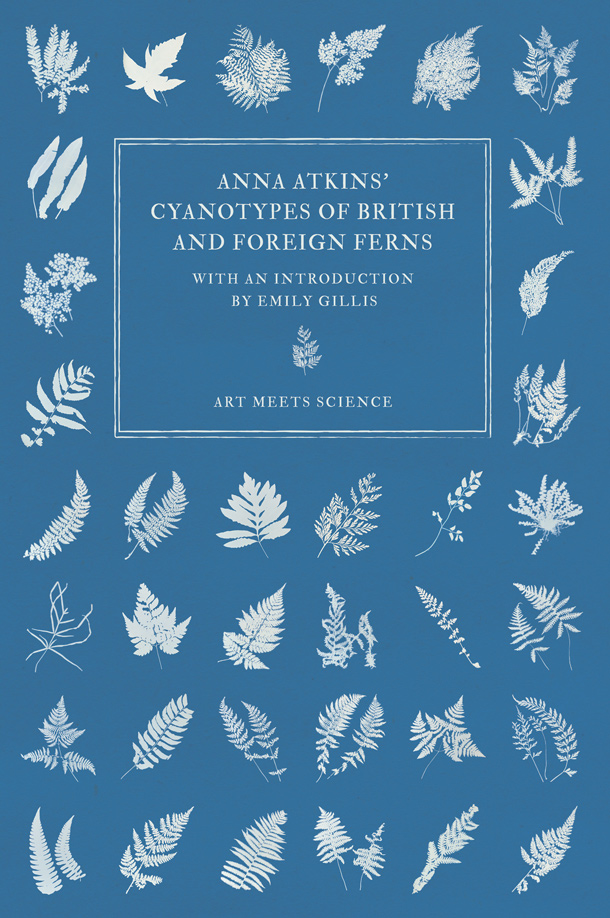

In a stunning celebration of early photography and the natural world, Anna Atkins‘ Cyanotypes of British and Foreign Ferns is a remarkable collection of botanical prints from the world’s first female photographer.

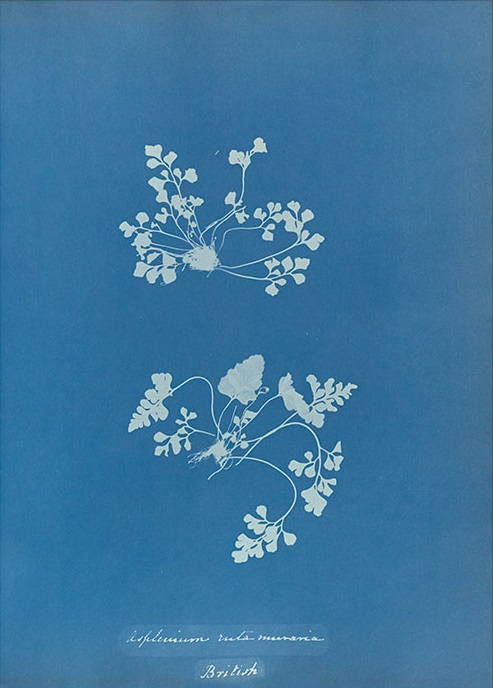

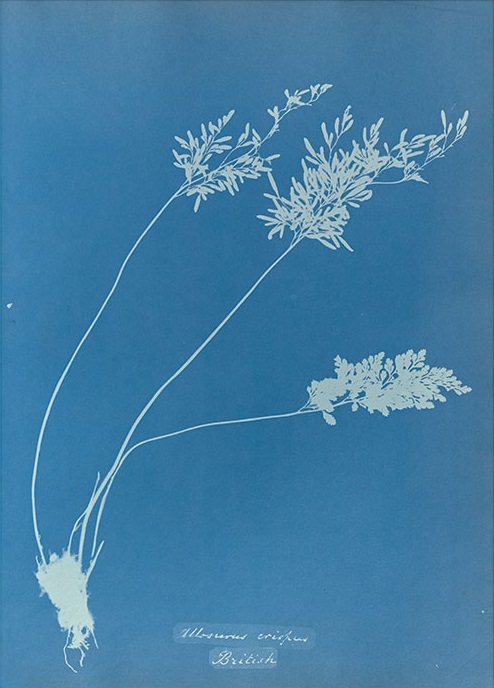

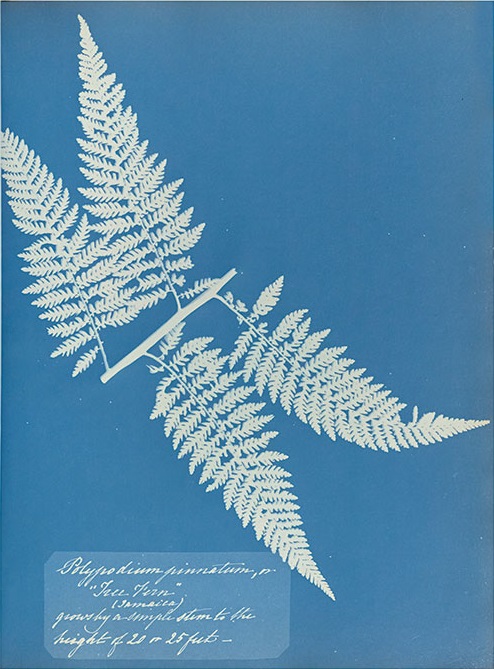

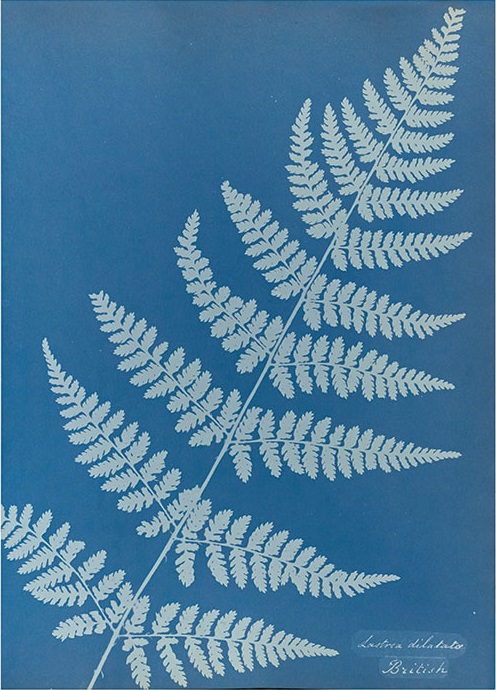

First published in 1853, this volume is an immersive showcase of unique botanical prints. The cyanotypes featured in this book are some of history’s first photographs, capturing British and foreign ferns in deep Prussian blues and crisp whites. Delve into the history of Anna Atkins’ cyanotypes, and discover a landmark feat of scientific illustration and publishing in the latest addition to our Art Meets Science collection.

Anna Atkins: The First Female Photographer

Anna Atkins was an English botanist and photographer. While little is known about her personal life, she is considered the first female photographer and the first person to publish a book illustrated with photographic images.

Born in Tonbridge, Kent, in 1799, Atkins was left an only child under her father’s care when her mother died shortly after giving birth. Her father, John George Children, was a well-regarded scientist specialising in chemistry, mineralogy, and zoology. He was an acting member of the Royal Society and British Museum, and it was through his network of scientific acquaintances that Atkins was exposed to a world kept separate from most women of the time.

At the turn of the century, only certain hobbies were deemed acceptable for women due to their gentile nature. Along with painting, sewing, and housekeeping, botany was popular due to its association with flowers and femininity. Boasting an unusually scientific education under the direction of her father and his friends, Atkins developed a passion for botany, collecting and studying specimens for her personal collection. In 1825 she married John Pelly Atkins, a merchant of India and railway promoter, which gave her the time and means to dedicate to her botanical interests. On her travels and through those of her friends, she collected rare specimens from around the world for her studies.

Corresponding mostly through her father, Atkins learnt much of her botanical knowledge through his friend and colleague Sir William Hooker, an established botanist and director of Kew Gardens. In a letter to Hooker on behalf of his daughter, Children states: ‘I am only the channel of communication. [Atkins] considers you as her tutor in botany, as what little knowledge she possesses in the science has been chiefly derived from your works.’

Her first foray into capturing botanical specimens followed the traditional method of recording by hand through drawing or painting, as she produced illustrations for her father’s translation of Lamarck’s Genera of Shells in 1823. Predating the advent of photography, authors relied on lengthy descriptions of specimens in their works to envisage their subjects, often pasting in hand-made illustrations and sketches or dried examples of specimens themselves, none of which provided comprehensive examples for their studies.

‘The unique outcome of each of the cyanotype prints lies in the personal touch of the hand that made them’

The Discovery of Photography

By 1839, the discovery of photography had been introduced in Britain by William Henry Fox Talbot, another close acquaintance of Atkins’ father. Through this connection, Atkins learnt first-hand about Talbot’s new photographic inventions. These included the photogenic drawing technique, where an object is placed on light-sensitised paper and uses the light from the sun to produce an image, as well as calotypes, a photographic method that uses paper coated with silver iodide that darkens when exposed to the light, creating an image in relief. Passages in Talbot’s journals reveal that he sent Atkins and her father his first memoir on photography along with some of his first photographic prints. This early access to the methodology of photographs allowed the pair time to practise and experiment with techniques, with Atkins’ father also providing her with one of the earliest cameras.

The photographic process that would become Atkins’ signature, the cyanotype, was developed by scientist and close family friend John Herschel in 1842 as an independent experiment on Talbot’s earlier methods. The process began by mixing two iron-based compounds, ferric ammonium citrate and potassium ferricyanide, brushing the mixture over the paper’s surface and leaving it in the dark to dry. The object to be photographed was then placed on the surface of the treated paper under a glass plate and exposed to sunlight for several minutes before the paper was washed with clean water and left to dry. A chemical reaction between the iron compounds, sunlight, and water, resulted in a brilliant pigment that revealed a Prussian blue negative of the object printed on the page. This method established by Herschel later became widely known as the ‘blueprint’ after it was adopted by the construction industry as a way to reproduce architectural drawings.

Herschel published details of his new technique in the Royal Society’s Philosophical Transactions publication, yet the specific chemical measurements of his method still needed to be specified. There were manuals and recipes to produce cyanotypes, but only some early photographers were successful in their attempts, with many unable to get the mix of chemicals right. Luckily for Atkins, through her close relationship with Herschel, she was able to learn the technique first-hand and reproduce it perfectly.

‘Each plant appears as if floating in water, the deep hue of the Prussian blue background providing an infinite depth in contrast to the delicate white details of each specimen’

The First of Anna Atkins’ Cyanotypes

In October 1843, Atkins published her first instalment of Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions with the illustrations intended to accompany William Henry Harvey’s Manual of British Algae, published two years previous. Her work changed the face of scientific documentation, and this landmark volume is regarded as the first book illustrated with photographic illustrations. She utilised the newest technology to create something never before seen in the publishing world.

Continuing to collect specimens and produce cyanotype impressions, Atkins created three volumes of British Algae between 1843 and 1853. It was a highly ambitious project, with the creative documentation of her botanical subjects taking over a decade to complete. She writes in the introduction to her first work:

‘The difficulty of making accurate drawings of objects so minute has induced me to avail myself of Sir John Herschel’s beautiful proofs of cyanotype, to obtain impressions of the plants themselves which I have much pleasure in offering to my botanical friends. I hope that, in general, the impressions will be found sharp and well-defined.’

Volumes of her botanical impressions were sent to various institutions such as the Royal Society and the British Museum, as well as contemporaries within her scientific network. Henry Fox Talbot, John Herschel, and Sir William Hooker received an early volume of the work, with each recipient responsible for organising and binding their own copy. Under 20 copies of Photographs of British Algae exist today, each unique in its order and number of prints due to the nature of the early publication.

‘Anna Atkins’ cyanotypes collection forms an immersive exploration of the ferns under inspection through each specimen’s tentative and artistic arrangement

Anna Atkins’ Cyanotypes of British and Foreign Ferns

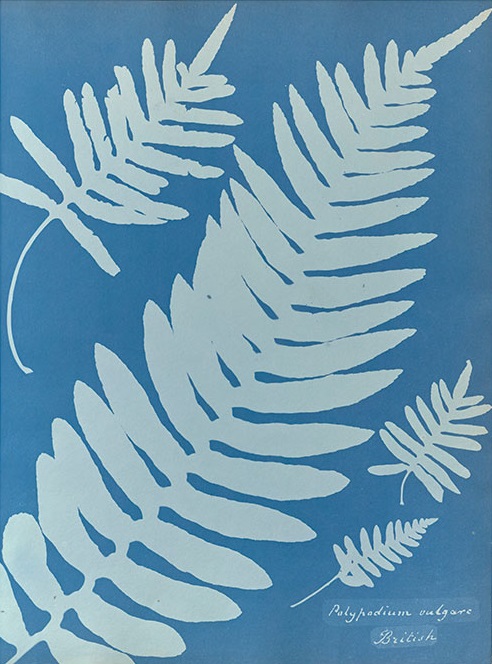

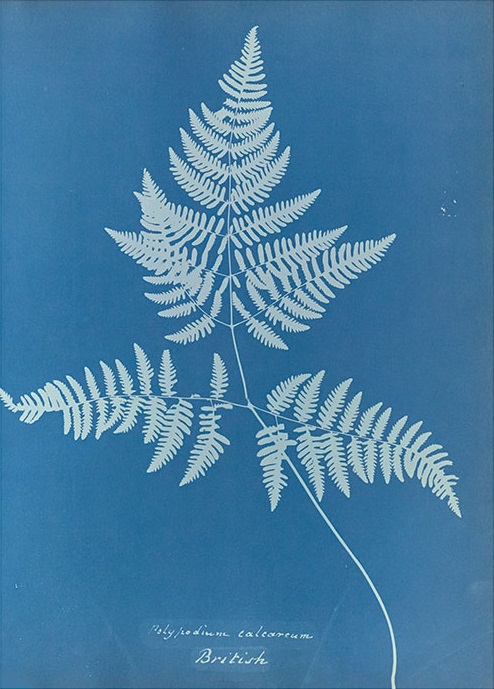

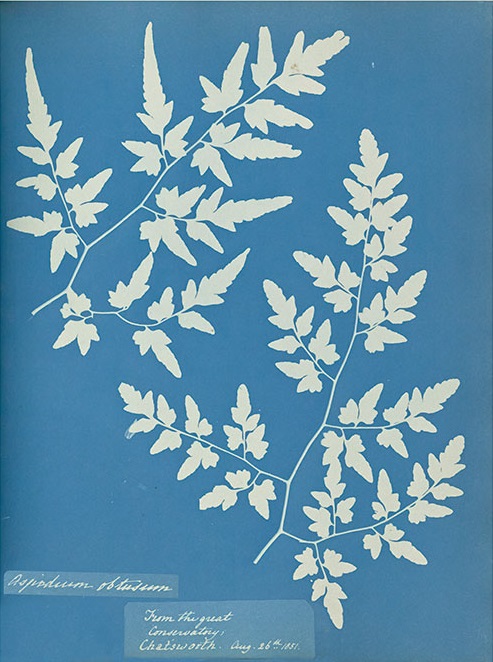

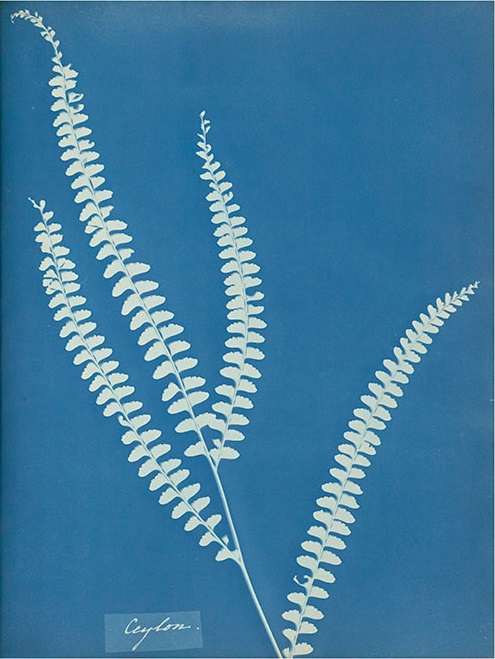

In the summer of 1853, Atkins, accompanied by her close childhood friend Anne Dixon, produced a second collection of blueprints entitled Cyanotypes of British and Foreign Ferns. Like the sprawling fronds of her algae impressions, Atkins arranged her fern specimens in an equally romantic style. The intricate details of each captured in the delicate images unfurl the magic of many common British ferns. However, the pair did not confine themselves to Atkins’ specimen collection, using their well-connected scientific circles and her husband’s travels abroad to pool samples from around the world.

Their stunning colour aside, the unique outcome of each of the cyanotype prints lies in the personal touch of the hand that made them. Mixing the chemicals and applying the solution by brush to each piece of paper, the washes of Prussian blue ebb differently on each sheet. This, combined with the unpredictability of the chemical reaction with the water as they dry and the individual touches that play a part in the systematic action of creating the prints, allow for a collection of impressions, each as unique as the next. Tiny white holes can be found in the corners of the images, where one can assume that Atkins pinned them up to dry. From the drip marks left by the water as it has run off the wet page in the drying process to the lighter circular smudge marks that appear when a fingertip has touched the chemical wash on the paper’s surface, Atkins left her mark on each and every page of her ambitious project, with her care and dedication to the process fundamentally apparent.

Each plant appears as if floating in water, the deep hue of the Prussian blue background providing an infinite depth in contrast to the delicate white details of each specimen. While they are impressions of static objects, the ferns hold an airy presence, their tendrils appearing in constant motion across the pages. Anna Atkins’ cyanotypes collection forms an immersive exploration of the ferns under inspection through each specimen’s tentative and artistic arrangement.

‘Atkins’ work changed the face of scientific documentation, utilising the newest technology to create something never before seen in the publishing world’

The Legacy of Anna Atkins’ Cyanotypes

As one of the first people to marry the worlds of science and photography, Atkins saw the importance of capturing the beauty of plants in a way that only the cyanotype process offered at the time. She was a pioneer of a new photographic process, developing a unique style of reproducing imagery. Her evanescent cyanotypes of algae and ferns artfully blend the worlds of botany and photography, creating a collection of Prussian blue impressions that would establish her as a catalytic force in both book publishing and scientific illustration.

Unlike her Photographs of British Algae, only two copies of Anna Atkins’ Cyanotypes of British and Foreign Ferns were produced of the same content and format, one of which now resides in the National Science Museum in Bradford while the other was sold to the J. Paul Getty Museum in 1984.

Despite creating a seminal publication in the worlds of both science and photography, little is known about the life of Atkins, as it seems that she communicated primarily through her father. While her beautiful compendium of algae was somewhat recognised around its time of publication, the volumes eventually fell through the cracks of history. She died at her home in Kent in 1871 at the age of 72.

In the 150 years since her death, Atkins’ unique work has only recently gained the recognition it deserves. The last few decades have seen celebrations of her blueprints at cornerstone institutions, with the New York Public Library hosting dual exhibitions to honour her historical achievements in photography and scientific documentation. While Atkins initially presented her volumes as objects of botanical observation, they have since become dynamic examples of early experimental photography.

Atkins’ contributions to art and science, not to mention publishing and technology, are now receiving the recognition they deserve. This facsimile edition of Anna Atkins’ Cyanotypes of British and Foreign Ferns captures the delicate magic of her vibrant botanical studies, taking care to reproduce the Victorian cyanotypes in their original state as a true celebration of this often-forgotten work.

Anna Atkins’ Cyanotypes of British and Foreign Ferns

Sign up for our newsletter to discover more of our beautiful books