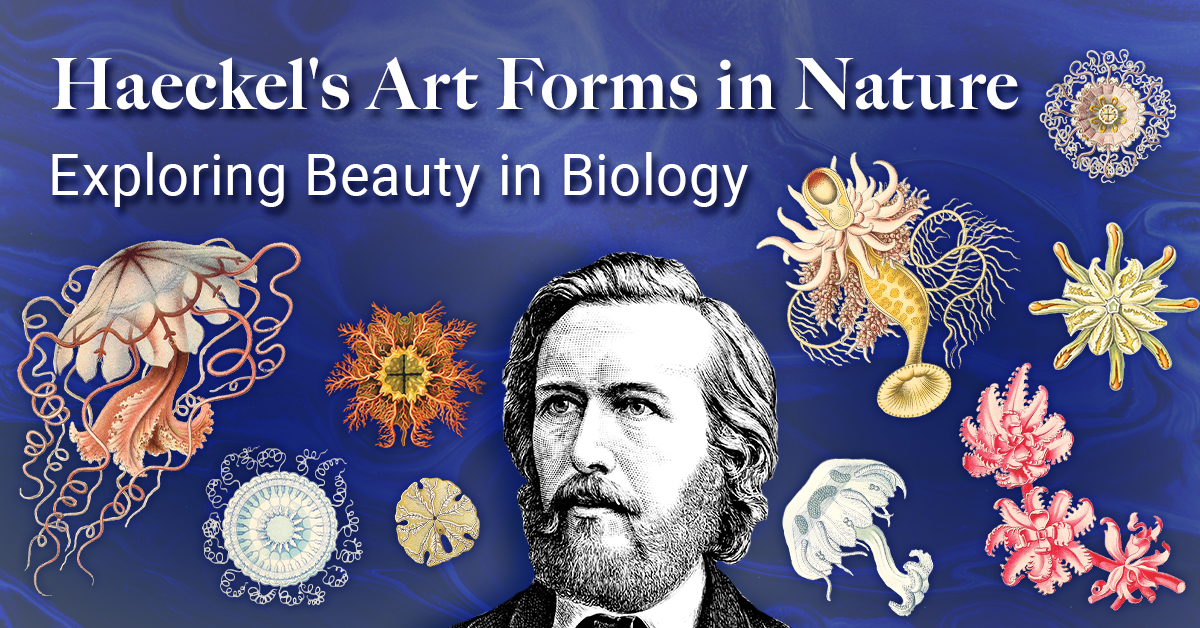

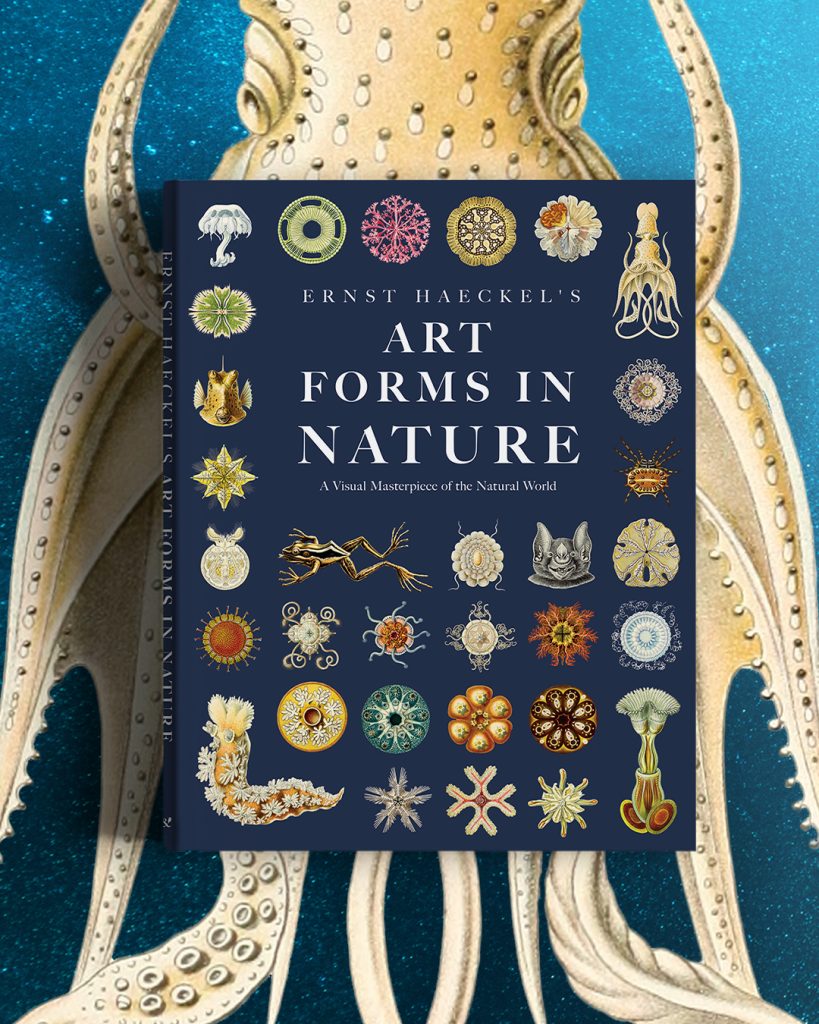

In a beautiful celebration of the natural world, Ernst Haeckel’s Art Forms in Nature is a masterful union of science and art.

As a proud addition to the Art Meets Science collection, Read & Co. Books has faithfully reproduced Haeckel’s innovative work. The volume is comprised of 100 illustrated plates, featuring stunning watercolour paintings and pencil sketches.

We’re diving inside this masterful work to give you a closer look.

Table of Contents

Kunstformen der Natur (Art Forms in Nature)

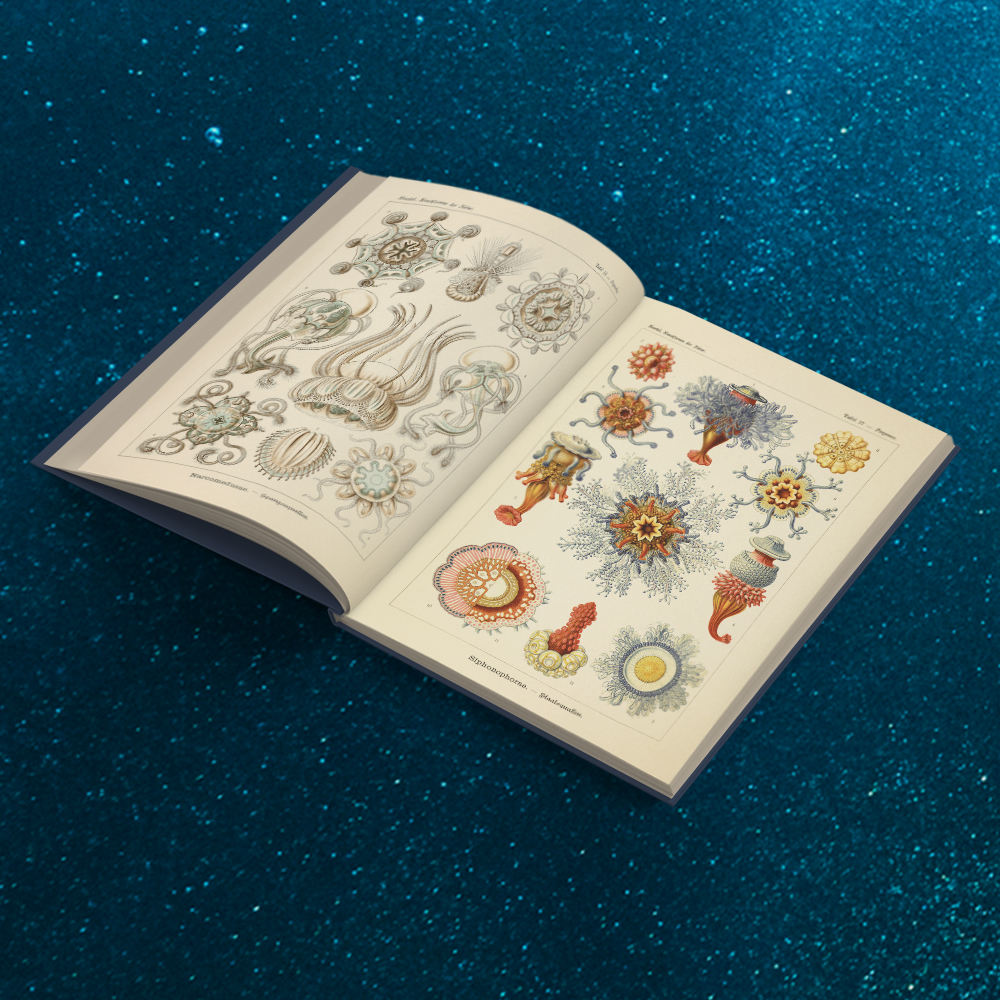

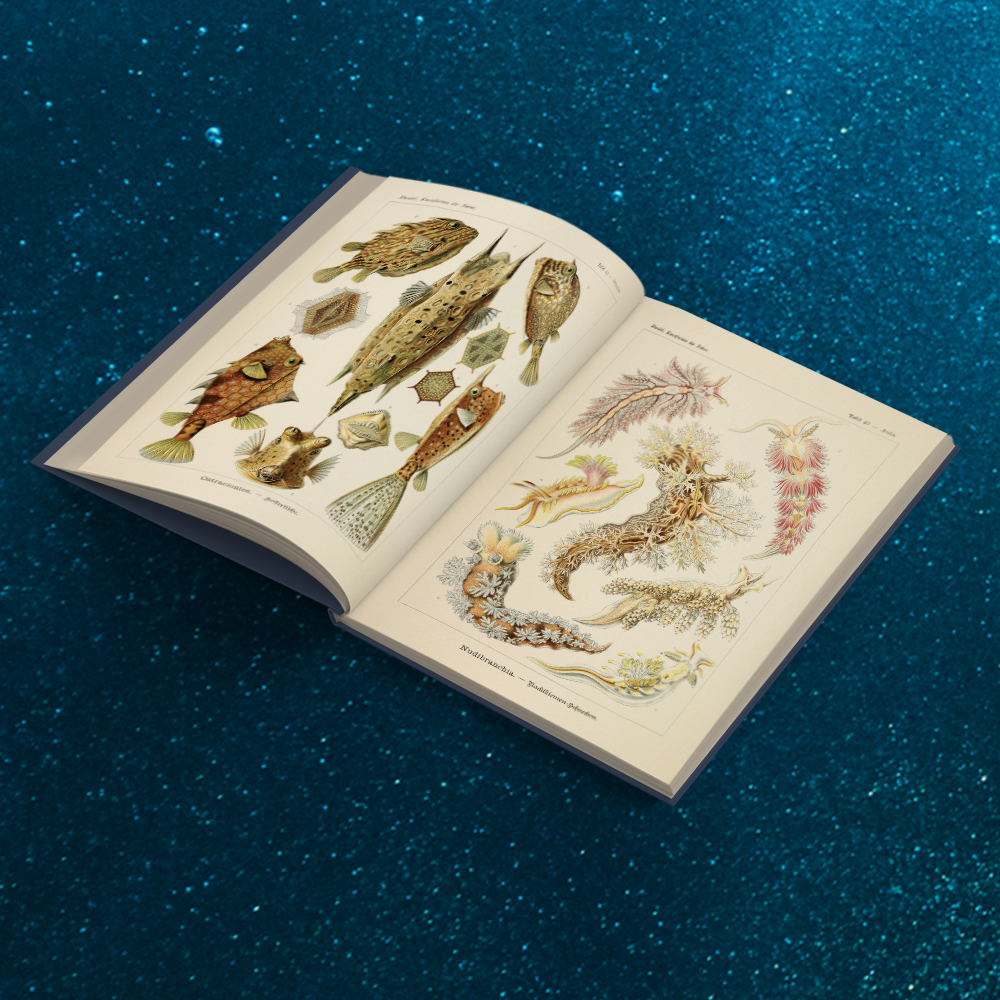

First published in 1904, Haeckel’s detailed illustrations serve as a visual encyclopaedia for his pioneering research and anatomical discoveries. Featuring stunning depictions of various land and sea life, including jellyfish, sea anemones, and Radiolaria (miniscule, soft bodied organisms), the sketches were translated into a series of lithographic and halftone prints for publication. Serving both a scientific purpose while boasting unparalleled aesthetic beauty, the unique collection of plates holds a lasting influence in both the art and science worlds.

Over a century since their first publication, the German scientist’s intricate prints remain an unparalleled study of microscopic organisms and advanced marine life. Originally published under the German title Kunstformen der Natur (Art Forms in Nature), his innovative volume was highly influential and helped to popularise the study of natural history.

Ernst Haeckel: The Scientist with an Artist’s Heart

Ernst Haeckel was born in Prussia on 16th February 1834. From an early age, he had a deep fascination with nature and the scientific principles of evolution, but his true passion lay in his artistic endeavours. Encouraged by his father to focus on his academic interests, he studied medicine in Berlin, Würzburg, and Vienna, before achieving his doctorate in 1857. He began working as a physician, but, unfulfilled by his work with patients, soon returned to his biological studies. In 1861 he earnt his habilitation in comparative anatomy – the highest university degree offered in many European countries.

In search of a project that would engage his passion for art as well as his interest in scientific research, Haeckel travelled to Italy. It was here that he met the German painter Hermann Allers. Inspired by his new friend, he realised he wanted to dedicate himself entirely to his creative desires. But, once again cautioned by his father, he was prevented from pursuing a full-time artistic career.

It was while Haeckel was in the Italian city of Messina that he received buckets of minute invertebrates from a local fisherman, which hadn’t been subjected to scientific investigation before. Studying the organisms beneath a microscope, he became enthralled by the sea creatures’ beauty and the remarkable geometry of their bodies, logging his discoveries through a series of sketches. Identifying them as Radiolaria, these tiny, single-celled organisms are classed as neither animals nor plants and had never been recorded in the intricate detail with which Haeckel worked. Viewing the organisms as nature’s own works of art, he captured the intrinsic details of their skeletons and bodies with dedicated precision. Here, he was able to combine his two passions, and within a single month he had identified over 100 new microscopic species.

Bridging the Gap Between Art and Science

Working in both pencil and watercolour paint, Haeckel rendered the natural beauty of the organisms he discovered, preserving their complex forms, patterns, and structures. Highlighting the naturally occurring symmetry of exoskeletons and epidermises, his illustrations focus on beautiful elements such as scale formations and molluscs’ spiralling patterns. The subtle shading and mesmerising attention to detail drew the public eye to thousands of previously unstudied species.

Utilising lithographic and halftone printing techniques, master lithographer Adolf Glitsch translated Haeckel’s illustrations into 100 highly detailed prints. The illustrations were collated into two volumes and published as Art Forms in Nature in 1904. The prints feature Haeckel’s beloved radiolarians, alongside many aquatic animals, such as corals, anemones, and jellyfish. The book’s striking images coupled with its innovative design inspired many artists of the time. At the turn of the twentieth century, the Art Nouveau movement was in full swing. The ornamental style took influence from the unruly spirit of nature, utilising the beauty found in natural forms, and drawing inspiration from the organic, flowing shapes of flora and fauna. This aesthetic style became widely adopted in various forms of applied arts, and in Germany it was referred to as Gesamtkunstwerk, meaning a complete or total work of art. Artists and designers like William Morris, glass artist Émile Gallé, and architect Antoni Gaudí were directly influenced by the natural forms, often using the imagery in their work. Among the many artists who utilised Haeckel’s biological illustrations is French painter René Binet, who paid tribute to Haeckel with his architectural designs, as well as his work in furniture, jewellery, and lighting, much of which was inspired by the microorganisms’ exoskeletons.

Ernst Haeckel and Charles Darwin

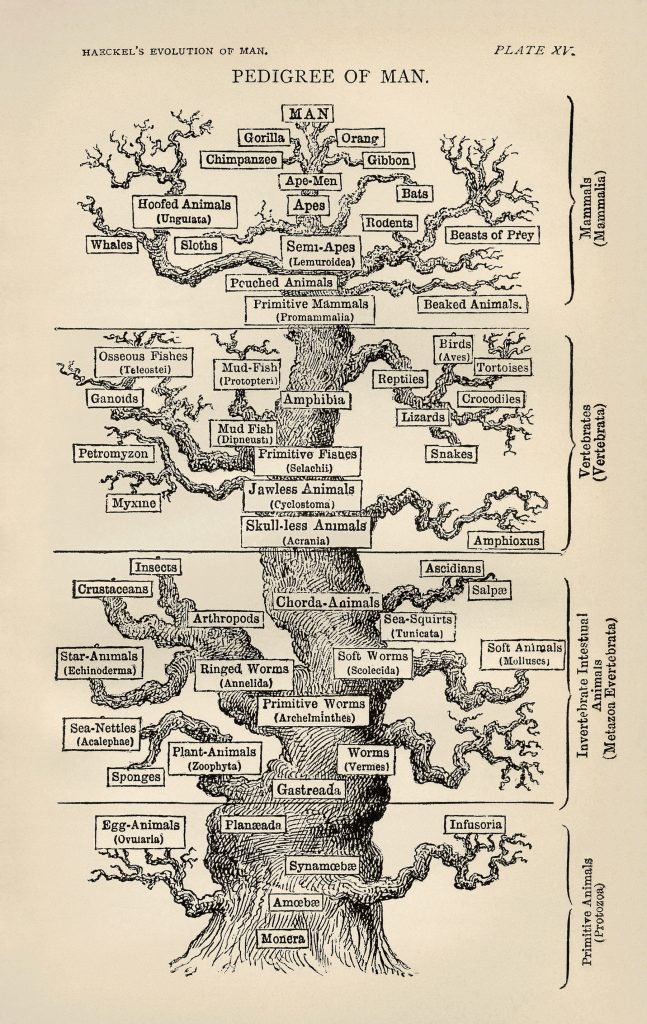

Art Forms in Nature not only inspired the art world but also helped to popularise the study of natural history. Haeckel’s botanical illustrations promoted the idea that science and art could be mutually beneficial and often complementary. His theories, coupled with his scientific sketches, became central to evolutionary theory, establishing him as one of Germany’s leading figures in popularising Darwin’s theory of evolution. He knew the intricate geometric patterns of Radiolaria held clues to the development of organisms. After reading the second edition of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species in 1860, he was eager to defend and promote the theory of evolution, then known as the Darwinian principle of ‘descent with modification’. In Generelle Morphologie der Organismen (1866), Haeckel stated that all advanced lifeforms stemmed from bacteria. In the late 1900s, this groundbreaking insight informed the development of the two-domain system – a biological classification that separates all organisms into either the bacteria or archaea domains.

In 1864, Haeckel sent Darwin copies of his white-on-black Radiolaria illustrations, and over a 20-year period, the men exchanged over 150 letters of correspondence. In 1873, Darwin wrote to Haeckel stating, ‘You will do a wonderful amount of good spreading the doctrine of Evolution, supporting it as you do, by so many original observations.’ The pair formed a strong working relationship, with Haeckel visiting Darwin at his Down House in England on three separate occasions.

Evolutionary Theory and Interrelationships in Nature

Haeckel became known as a pioneering biologist as well as an accomplished artist in his own right. He held a lecturing position at the University of Jena, Germany, as a professor of zoology for almost 50 years. On his retirement in 1909, he had published over 700 articles and 18 books. While lecturing, he made many short research trips to various parts of the globe, including the Cayman Islands, Norway, Russia, and Ceylon, discovering thousands of new micro species. He was highly influential in his academic field, successfully perpetuating the theory that nature can be best understood as a unification of many interrelationships. This idea led to his coining the term ‘ecology’, stemming from oikos, the Greek for household. He penned many other words still in use today, such as Protista (the group name for unicellular organisms) and phylogeny, referring to the evolutionary interconnectivity of all species. Developing a phylogenetic tree of life, he formed a metaphorical model displaying the pattern of universal common descent. Placing mankind at the peak of the tree, the diagram traces all life on Earth to a single ancestor.

The Legacy of Art Forms in Nature

Art Forms in Nature remains a beloved and influential work, admired for its combination of scientific accuracy and artistic beauty. The volume made a remarkable contribution to the fields of biology, art, and design, broadening our comprehension of the relationships between different forms of life. Over a century after their first publication, Haeckel’s elaborate lithographic, halftone prints continue to be an exceptional biological exploration, successfully marrying art and science.

Preserving Haeckel’s Art Forms in Nature

This facsimile edition features the complete collection of Haeckel’s 100 original plates. The biological sketches and paintings are categorised according to their genus, and this is reflected in the index included at the back of the volume. The index lists the Latin names of all the organisms depicted in each plate, accompanied by the scientists and researchers who first discovered and identified the respective life forms. Some of the classifications are now redundant due to modern discoveries and revised taxonomy.

As a proud addition to the Art Meets Science collection, Read & Co. Books has faithfully reproduced Haeckel’s innovative work. Taking care to conserve the original detail, shapes, and colours as they were printed on initial publication, this beautiful volume recaptures the magic of Art Forms in Nature for a new generation to enjoy.

Discover more from Art Meets Science