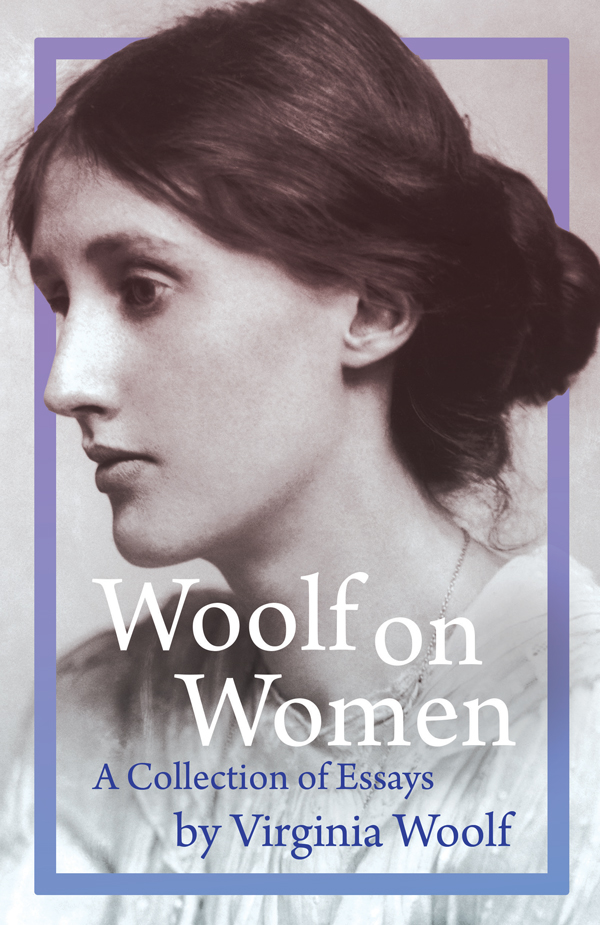

Virginia Woolf, women, and writing often come in the same breath, and with much of her work exploring her feminist views, it’s not surprising. She’s best known for her commentary on the inequality between men and women, with her seminal essay ‘A Room of One’s Own‘ being her personal feminist manifesto, inspiring many generations to come. Her arguments often regard the differences in the legal and economic power of the sexes, while passionately discussing women’s future in society and education.

Woolf’s work was central to the second wave of feminism in the 1970s and continues to inspire feminist ideas today. In the essays featured in the Woolf on Women collection, she discusses female writers and women in society and fiction, taking inspiration from the likes of George Eliot, Jane Austen, and the Brontë sisters. She shares her political and societal views and showcases her appreciation for the great women with whom we now regard her.

In 1869, Woolf gave a lecture to the undergraduate women at Girton College, Cambridge, and later, in 1871, she also addressed Cambridge’s undergraduate women in the Arts Society at Newnham College. These lectures eventually became the famous essay ‘A Room of One’s Own‘ (1929), in which she lays bare her raw and unashamedly honest opinions on the problems of being a woman writer. The work summarises many of the conclusions she draws in her other writings on women. One of her key points is that excellent fiction is not the result of high intelligence or a particularly great mind but instead the result of the writer’s material circumstances. In the nineteenth century, particularly, being born a man was an advantage because they had access to education, whereas women could barely read, spell, or even speak for themselves. This, Woolf concludes, is the reason for the severe lack of women writers. She explains that women need freedom and independence to write. In her opinion, this equates to a room of one’s own (and £500 a year, which is equal to around £19,000 in today’s money). It was not until 1948, decades after Woolf presented these lectures, that women studying at Cambridge were finally allowed to be awarded degrees.

In many of her essays, Woolf refers to women writers she greatly admired and respected. But she believed that despite the success of their work, they still did not have proper or complete freedom because they wrote behind male pseudonyms and, therefore, lost their identity. One such writer is George Eliot (1819–1880). Eliot, or Mary Ann Evans, was an English novelist, poet, and journalist who wrote behind a male name to try and escape the stereotype that women can only write inconsequential romance novels. She also wanted to keep her private life away from scrutiny and the public’s prying eyes due to her adulterous affair with English philosopher and critic George Henry Lewes. Eliot’s well-known novel, Middlemarch, explores themes of women and ambition. It reflects Eliot’s own beliefs that ‘women are always in danger of living too exclusively in the affections; and though our affections are perhaps the best gifts we have, we ought also to have our share of the more independent life – some joy in things for their own sake.’ Woolf stated while commenting on Middlemarch that it was ‘one of the few English novels written for grown-up people’.

“A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.”

Virginia Woolf

While many women writers were surviving in the shadows, a few broke through to celebrity status. Despite being dependent on their constructed male identities, they explored some key feminist themes throughout their work. A fine example of this is the Brontë sisters. Also using male pseudonyms, Charlotte, Emily, and Anne Brontë were English poets and novelists, frequently writing under Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell. The eldest sister, Charlotte Brontë (1816–1855), was best known for her second novel, Jane Eyre (1847). The novel’s first-person account from the perspective of an ordinary governess was ground-breaking. It gave a long-overdue voice to all women who lived a ‘curious silent unrepresented life’, as Woolf writes in The Voyage Out (1915). R. B. Martin labelled Jane Eyre the first major feminist novel, and its explorations of the patriarchy’s entrapment of women in domestication are still referred to in modern literature. Similar feminist themes appear in the works of the two younger sisters, Emily and Anne, as they explore a woman’s place in the world and defy pre-constructed societal norms of the time. The Brontës were a great source of inspiration for Woolf, and in 1925, she stated that ‘Wuthering Heights is a more difficult book to understand than Jane Eyre because Emily was a greater poet than Charlotte… She looked out upon a world cleft into gigantic disorder and felt within her the power to unite it in a book.’ The sisters’ works are among the first examples of feminist literature, depicting strong, wilful women, and making space for otherwise disregarded narratives in a male-dominated world.

Continuing with the theme of early feminist writings, the English author Jane Austen (1775–1817) was a significant influence on Woolf. Known for her biting social-commentary novels, Austen used irony and comedy in her classic Regency romances. She wrote satirical stories that did not conform to Romantic stereotypes or the themes of sentimentality found in many books of the time. Similarly to Woolf, her work critiques the socio-economic standing of women during her lifetime. It highlights the unfairness of women’s dependence on marriage – a subject about which Woolf was passionate. In the essay ‘Jane Austen’, Woolf describes her as ‘the most perfect artist among women, the writer whose books are immortal’. Woolf was aware of the disruption that Austen brought to the male literary scene, despite her early death, aged 42. Her final writings would almost certainly have demonstrated an evolution in her style and voice but were abandoned as just fragments of her imagination.

Another work by a nineteenth-century female writer Woolf draws upon is that of Pre-Raphaelite poet Christina Rossetti (1830–1894). Part of the Pre-Raphaelite literary movement and influenced by Romanticism, Rossetti was an English poet and a strong inspiration for Woolf. Her work is often viewed as a response to a repressed soul bound by religion and a strict sense of duty to God. It’s commonly argued that her relationship with God restricted her life and limited the pleasures she allowed herself to experience. Woolf describes her poetry as being ‘full of gold dust’ but comments on the ‘dark’, ‘harsh’ God who resided in ‘the centre of Christina Rossetti’s being’. She suggests the poet would have lived a happier life outside the confines of her faith, but if this had been the case, some of the most praised poems in literary history might have never been written.

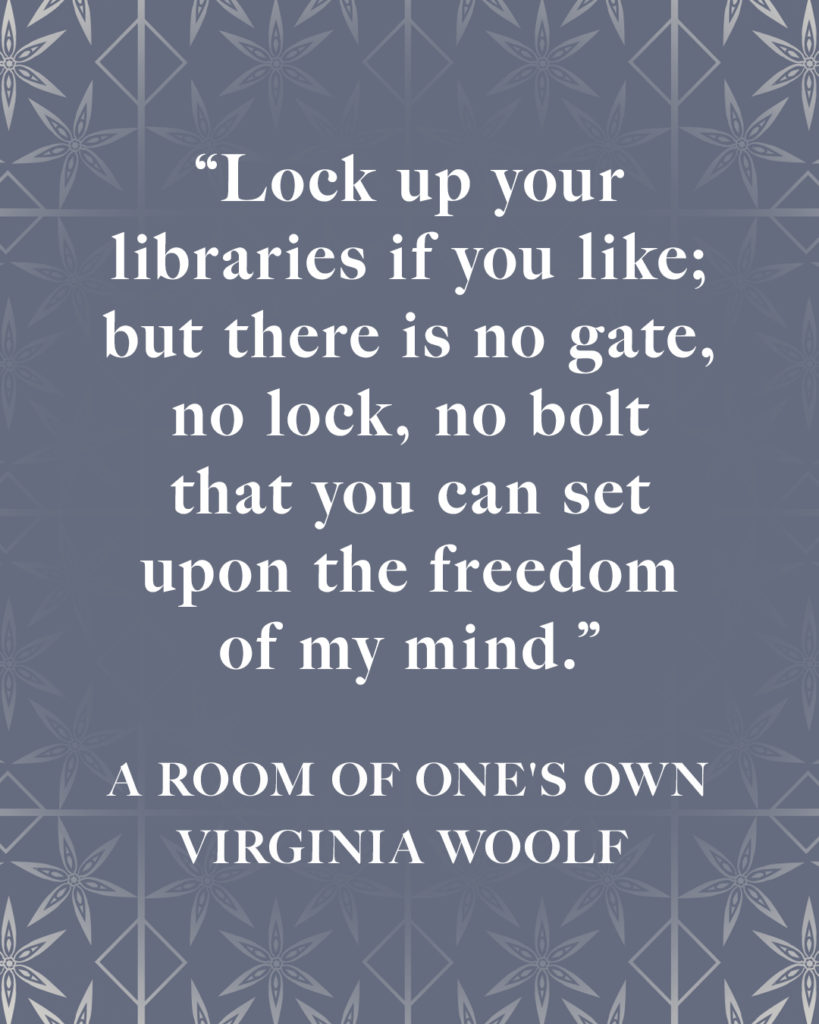

“Lock up your libraries if you like; but there is no gate, no lock, no bolt that you can set upon the freedom of my mind.”

Virginia Woolf

Alongside Woolf’s feminism, her sexuality is commonly mentioned in writings about her and her work. She was openly bisexual and had multiple relationships with women during her lifetime, stating numerous times in letters that she is not physically attracted to men and prefers to have sexually intimate relationships with women. It may be said that Woolf’s sexuality and feminism are tightly woven, so it would be difficult to remark upon one and not the other. The idea that feminism and female sexuality are tightly bound is also present in the work of Louisa May Alcott (1832–1888), most famous for her novel Little Women (1868). Alcott was an American novelist, strong abolitionist, and inspiring advocate for feminism.

She was the first woman to register to vote in Concord, Massachusetts, USA. She made her passionate feminist views clear in her writing, mainly through Little Women’s wilful, hot-headed protagonist, Jo March. Alcott’s sexuality has been the subject of speculation, with many scholars believing her to have been homosexual. Although there is no evidence that the novelist was in any relationships with men or women, she did state in an interview, ‘I am more than half-persuaded that I am a man’s soul, put by some freak of nature into a woman’s body… because I have fallen in love in my life with so many pretty girls and never once the least bit with any man.’ A very similar standpoint to that of Woolf.

In her work, Woolf writes about women with strong admiration. Her essays feature many other notable women such as feminist and suffragist Emily Davies, writer and Woolf’s step-aunt Anne Isabella Thackeray, author and dramatist Mary Russell Mitford, and her friend and one of the greatest English poets Elizabeth Barrett Browning. She discusses the lives and works of often forgotten women, like those related to the Lake Poets, including William Wordsworth’s sister, Dorothy Wordsworth, and Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s daughter, Sara Coleridge. Commenting on issues of socio, economic, and political equality, Woolf studies and champions some of the most notable women throughout history, as well as the lesser-known greats who lived quiet lives in the shadows of men.

Woolf on Women – A Collection of Essays by Virginia Woolf

Woolf on Women is a collection of Virginia Woolf’s essays about women (fictional, historical, and those Woolf knew personally). This volume features essays that were published between 1924 and 1941 (the year of Woolf’s death), and includes work that was published posthumously. This book allows readers to catch a glimpse into Woolf’s mind, particularly her political, social, and socio-economic opinions. It contains famous works such as ‘A Room of One’s Own’. An essential read for fans of Woolf and those who want to take a deeper dive into her thoughts, this book is also the perfect gift for lovers of feminist literature.

Loved this post? Say it with a pin!