Philip Edward Thomas was born in Lambeth, London, England in 1878. His parents were Welsh migrants, and Thomas attended several schools, before ending up at St. Pauls. Never entirely happy with urban life – he took many trips to Wiltshire and Wales, fostering an attraction to the natural world which would inform much of his later poetry – Thomas led a reclusive early life, and began writing as a teenager. He published his first book, The Woodland Life (1897), at the age of just nineteen. A year later, he won a history scholarship to Lincoln College, Oxford.

In 1899, while still an undergraduate, Thomas married Helen Noble, daughter of the essayist and poet James Ashcroft Noble (1844-1896). Encouraged by his wife's father, Thomas committed himself to becoming a man of letters. He worked frantically, reviewing up to fifteen books a week (usually poetry collections) for the Daily Chronicle, and penning six collections of essays in eight years. Thomas was a skillful critic; in 1913, The Times described him as “the man with the keys to the Paradise of English poetry.” He also became a close friend of the Welsh poet W. H. Davies, whose career he almost single-handedly developed.

Thomas was never entirely happy with life as a prolific essayist, however. In correspondence with the poet Gordon Bottomely, he described himself as a hack writer, a “hurried and harried prose man” whose exhaustion left his brain “wild.” Thomas suffered from chronic depression, apparently carrying a vial of poison (which he described as his “saviour”) with him at all times. In 1911, he suffered a severe mental breakdown.

In the spring of 1914, in what was arguably the most formative event of his life, Thomas met the American poet Robert Frost. Although Frost is now one of America’s most adored poets, at this point no one would publish his work in the United States, and he had emigrated to England in search of artistic fortune. Thomas had previously reviewed Frost's work at great length, and, upon meeting, the men engaged in lengthly discussions on the nature and form of poetry.

On one of their many long countryside walks, Frost suggested to Thomas that sections of his In Pursuit of Spring (1913) – a meditative travelogue documenting Thomas' pilgrimage by bicycle from Clapham Common, London, to the Quantock Hills of Somerset – might be turned into poems. Together, the two men experimented with composing lines that followed, in loose poetic form, the sound-patterns of speech – building on theories of rhythm and form Thomas had expressed in his critiques of Algernon Charles Swinburne (1912) and Walter Pater (1913).

Frost's advice turned out to be transformative. Thomas returned to his accumulated writings with new imagination. He began to pen loose and lyrical poems, calling them “quintessences of the best parts of my prose books” which purged the stultifying effects of “damned rhetoric” from his writing. As well as being a creative release, Thomas found the process of writing poetry to be highly therapeutic; in his journals, he spoke of them as fostering a sense of strong mental calm.

Thomas began writing poetry seriously in December of 1914 – five months after the onset of World War I. He published several poems under the pseudonym Edward Eastaway, which variously baffled and delighted reviewers. Meanwhile, he deliberated over whether to join the war effort or not (Frost penned what would become his most famous poem, “The Road Not Taken”, in response to Thomas’s dilemma).

Eventually, despite being overage, Thomas enlisted in a voluntary unit in July 1915. He then returned to his poetry with a renewed vigour. However, Thomas was not a war poet in the same sense as Wilfred Owen or Siegfried Sassoon – the trenches barely feature in his work, and he only wrote one poem after reaching France – nor was he any less conflicted than these men about the conflict. For Thomas, World War I compounded a range of complex feelings he harboured regarding England, the countryside, culture and identity. Speaking of his enlistment in the essay 'This Is England', he said “Something, I felt, had to be done before I could again look composedly at English landscape.” However, he stressed elsewhere that “I hate not Germans nor grow hot/ With love of Englishmen, to please newspapers.”

In November 1916, Thomas was commissioned into the Royal Garrison Artillery as a second lieutenant. Soon after arriving in France, Thomas was involved in the Battle of Arras, a British offensive. On Easter Monday (9th April), while standing to light his pipe, one of the last shells fired during the battle landed close to him, causing a concussive blast from which he didn't recover. He was aged 39.

Despite being less well-known than other World War I poets, Thomas is regarded by many critics as one of the finest. Since the seventies, five new anthologies of his verse have appeared (the vast majority of Thomas' work wasn't published during his brief literary life), and the longtime British Poet Laureate Ted Hughes went so far as to call him the “father of us all.” In 2011, a biography of Thomas by Matthew Hollis entitled Now All Roads Lead to France: The Last Years of Edward Thomas won the Costa Biography Award.

In 1985, Thomas was among sixteen World War I poets commemorated on a slate stone unveiled in Westminster Abbey's Poet's Corner. Meanwhile, in Steep, East Hampshire – where Thomas and his wife lived between 1913 and 1916, and where he composed the bulk of his poems – a memorial stone has been erected to the memory of the poet. The stone's inscription includes the final line from his essay collection, Light and Twilight (1911):

“And I rose up and knew I was tired and I continued my journey.”

Beautiful Books to Buy for Nature Lovers this Christmas

Beautiful Books to Buy for Nature Lovers this Christmas

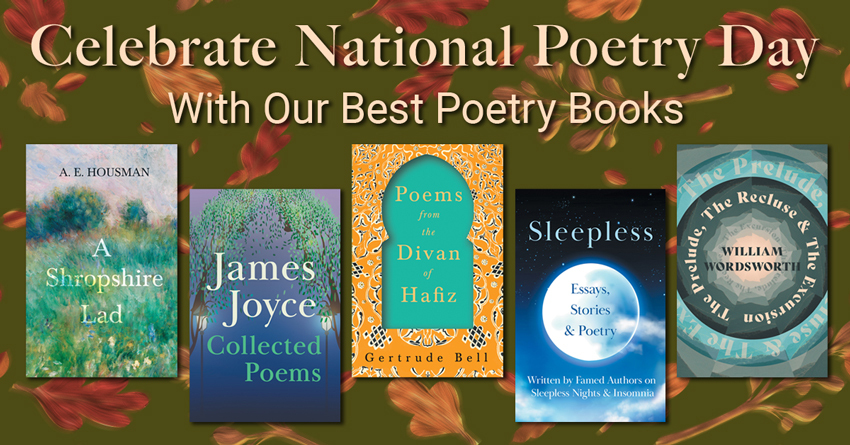

Celebrate National Poetry Day With Our Best Poetry Books

Celebrate National Poetry Day With Our Best Poetry Books